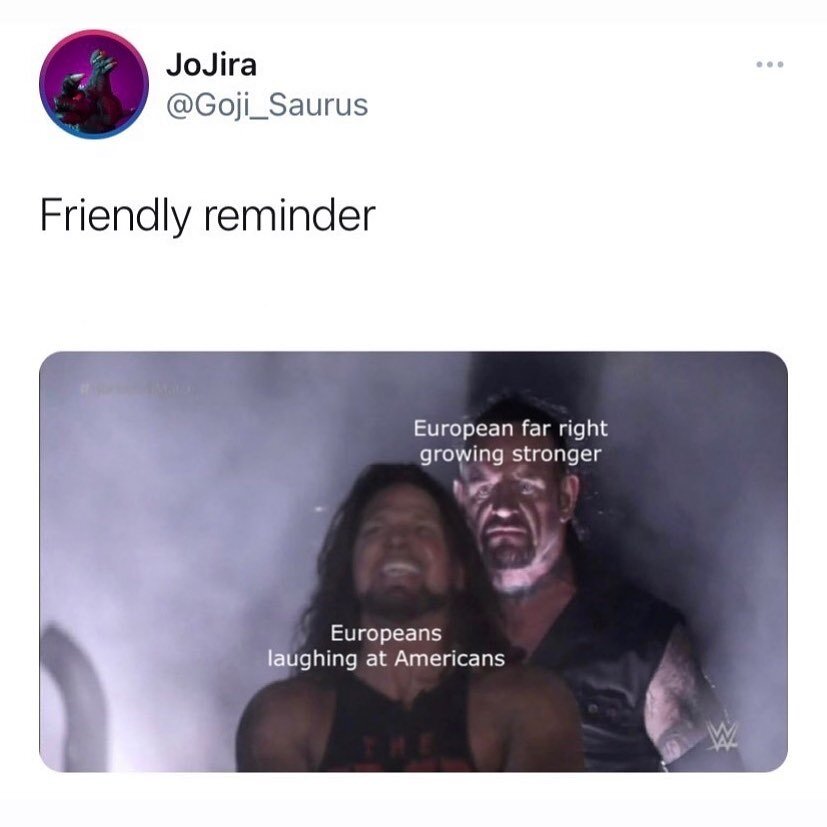

BB : Dans de nombreux pays d'Europe comme la Pologne ou la Hongrie, on voit actuellement une restriction des droits, souvent justifiée ou accélérée par la pandémie. Nous voyons des restrictions à la liberté de la presse, à la liberté de réunion et aux droits de l'homme. Quel rôle l'art peut-il jouer dans le mouvement de résistance en Europe ?

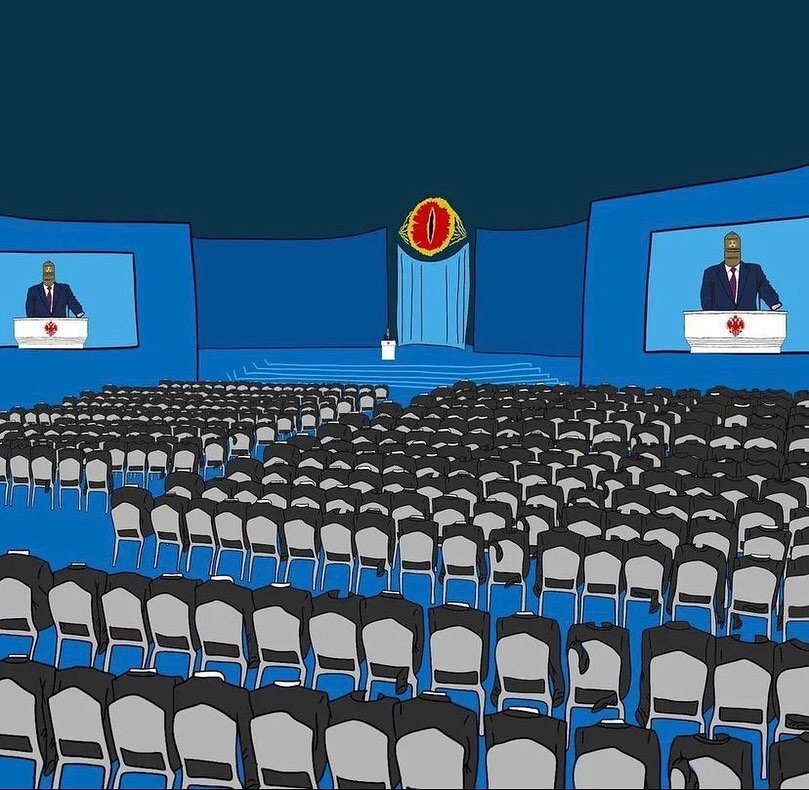

MR : Ce qui m'a toujours beaucoup aidé, c'est la solidarité, le fait de montrer que l'on n'est pas seul. Le pouvoir étatique fonctionne toujours avec des essentialismes, les gens sont racialisés, essentialisés selon leur origine, leur genre, leur religion, isolés. De sorte qu'ils ont l'impression d'être montrés du doigt précisément à cause de cette qualité, la couleur de leur peau, par exemple - et ils cherchent la faute en eux-mêmes. L'Holocauste et les processus de désolidarisation de la société en général ont fonctionné parce que les gens ne se sentaient plus concernés par ce qui arrivait aux autres. Les campagnes de haine fonctionnent toujours par le biais de la stigmatisation et, au final, tout le monde pense que les opprimés, les marginaux sont essentiellement responsables de ce qui leur arrive - ou du moins, ils restent silencieux lorsque quelqu'un est piégé.

BB : Quel rôle l'art joue-t-il dans la prévention de ces tactiques ?

MR : L'art peut créer la solidarité et l'identification par la politique de l'image. Qu'à l'aide de concepts généraux, d'images et d'histoires, par exemple par l'histoire de Jésus, on réalise soudain qu'il s'agit d'une histoire entièrement humaine qui se déroule aujourd'hui et qui nous concerne tous. Et vous ne pensez pas que ce qui se passe en Pologne se passe en Pologne, ce qui s'est passé dans les années 40 ne s'est passé que là. Le temps et l'espace n'existent pas en tant que topographie artistique. L'art peut être contre-historique, l'art peut entrer en contact avec les morts, l'art peut parler de ce qui n'est pas encore arrivé. L'art peut être une utopie, et l'art peut en même temps laisser cette utopie prendre place dans la réalité absolue, émotionnelle et collective d'un projet de théâtre et d'une soirée de cinéma. L'art peut avoir un effet direct et, en même temps, il est absolument fictif. Réunir la réalité et l'utopie, la pratique et l'espoir, voilà ce qu'est l'art.

BB : Voyez-vous un danger dans le fait qu'à une époque comme aujourd'hui, où l'art ne se produit pas de la même manière, où les scènes sont toutes fermées, où les gens ne peuvent pas sortir dans la rue et se rassembler, il devient plus facile pour les dictateurs et les autocrates d'influencer les systèmes ?

MR : Oui, dans les crises les droits sont toujours remis en cause. Les crises sont régressives, le plus conservateur, le plus destructeur est mis en jeu contre la destruction vécue. Les crises et les guerres déshumanisent la façon dont les gens se traitent les uns les autres. Le problème est surtout que l'art est retiré du contexte de la vie. Assister à une répétition, à une pièce de théâtre, être ensemble après et en parler, c’est ça, le vrai processus, qui m'intéresse. Ce n'est pas une séance où l'on va avec le masque sur le visage où l’on consomme quelque chose de créatif sans trop se rapprocher les uns des autres. La séparation de la vie et de l'art est l'une des nombreuses stratégies capitalistes d'aliénation qui existent depuis des siècles, elle n'a donc rien d'exceptionnel, mais en ce moment, nous la voyons dans sa forme la plus pure, pour ainsi dire : vous achetez un billet, entrez dans un online chat room et regardez d'autres personnes qui vivent ailleurs. Comme je l'ai dit, c'est le capitalisme dans sa forme la plus pure : l'art devient un bien de consommation, le corps de l'autre devient l'objet d'une observation distante. Or, le théâtre consiste précisément à faire entrer les corps dans un contexte de pratique vivante et utopique. C'est ce qui a été brutalement perdu au cours des 13 derniers mois. On ne grandit et ne change que par rapport aux autres et avec eux.

BB : Faites-vous actuellement l'expérience d'une plus grande solidarité au-delà des frontières nationales ?

MR : Oui et non. Au début, il y avait une forte tendance à la nationalisation, et aujourd'hui encore, il y a une fragmentation fédérale extrême, même en Allemagne. Il y a eu une désolidarisation, pas nécessairement consciente, mais simplement parce que les structures de solidarité à long terme - telles que les allocations de chômage, l'assurance maladie, sont nationales. C'est un problème général, qui se manifeste également dans la lutte contre le changement climatique ou dans l'industrie des biens.

Les coûts à long terme sont aussi désormais externalisés dans le Sud. Les personnes situées au début de la chaîne de production ne peuvent pas soudainement arrêter de produire du coton ou du coltan pendant quelques mois simplement parce que les T-shirts ou les ordinateurs ne sont pas nécessaires. Ils n'ont pas d'industrie de transformation et ne peuvent rien faire de ces matières premières si on ne les leur prend pas. Du côté positif, cependant, nous avons également remarqué à quel point ces États-nations étaient puissants, du moins au début, et quelles exigences extrêmes un État-nation peut imposer à ses citoyens et aussi à son économie. Cela peut sembler un peu étrange, mais cette discipline rationnelle des citoyens, qui pensent dans des contextes plus larges et font également preuve de solidarité, me rassure à l'ère du changement climatique, où seule l'action collective peut apporter quelque chose.